MF DOOM

Why the Villain Matters

Hip-hop has always rewarded visibility. Faces on posters, names in lights, charisma turned into profit. MF DOOM chose the opposite. He erased his face, buried his name, and still built one of the most enduring myths the culture has ever seen.

The mask was more than costume, it was a form of rebellion. DOOM wore it to keep the focus on music rather than image. “The mask really represents rebelling against trying to sell the product as a human being. It helps people focus more on what’s being said,” he explained in a rare interview.¹ In a world that measured rappers by image, DOOM refused to be measured at all.

The mask also gave him freedom. Behind the metal faceplate, Daniel Dumile fractured into new personas: MF DOOM, King Geedorah, Viktor Vaughn, Madvillain (with Madlib), DANGERDOOM (with Danger Mouse), JJ DOOM (with Jneiro Jarel), NehruvianDOOM (with Bishop Nehru), and Metal Fingers for his producer work.

Each identity showed a different cut of his creativity, a new voice, another mask, another pour. Collaboration was part of the mythology, extending from the aliases to full projects with others who understood the character, from Madvillainy to Czarface Meets Metal Face.

For us, DOOM is the foundation. He is the reason hip-hop never left rotation after the golden era, the reason this project exists at all. He proved that music could be myth and that craft could outlast image. DOOM matters because his legacy stayed real and outlasted anything the culture could package.

Song: “All Caps” (Madvillainy, 2004)

Pour: Lagavulin 8 Year Old Islay single malt, 96 proof.

Both open with smoke. The track sounds sharp and minimal, all edges and rhythm. Lagavulin 8 carries the same discipline, peat over sweetness, proof over polish. Each leaves nothing to hide behind.

Origins – Zev Love X and KMD

Before the mask and before the villain, there was Zev Love X. Daniel Dumile, his younger brother DJ Subroc, and MC Onyx the Birthstone Kid formed KMD (Kausing Much Damage) in Long Island in the late 1980s. Their sound fit the Afrocentric wave of the time: playful, political, steeped in Five Percent Nation influence, yet carried by humor.

Their debut Mr. Hood (1991) was stitched together from unusual sources, pulling from language records, cartoons, and loops of jazz and funk. Zev’s voice was sharp but light, mischievous, a young MC who could turn consciousness into comedy without losing its edge. They stood alongside groups like A Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul but carried their own satirical bite. KMD crossed paths with 3rd Bass and MF Grimm, early affiliations that shaped their circle.²

By 1993, they were ready to release their second album, Black Bastards (unreleased in 1993, issued in 2000). The cover art showed a cartoon figure being lynched, a biting critique of systemic racism. Elektra Records called it too controversial and dropped the group.³ At around the same time, tragedy struck when DJ Subroc was killed crossing the Long Island Expressway.⁴

Within weeks, Dumile lost his brother and his career. He withdrew from the scene, absent from public life for years. The loss ended one chapter of his life and left a silence that lasted years. KMD showed his ability to weave satire, politics, and playfulness into one voice, even before the mythology that would later define him.

Song: “Who Me?” (Mr. Hood, 1991)

Pour: Evan Williams Bottled-in-Bond Kentucky Straight Bourbon, 100 proof.

Zev’s humor moves quick, each bar light but precise. Evan Williams Bottled-in-Bond works the same way, clean grain under a steady burn. Both feel familiar but carry more structure than first expected.

Rebirth as the Villain

After years away from the public, Daniel Dumile reappeared in New York clubs in the late 1990s. His hood was pulled low, his face hidden, his voice roughened by silence. Crowds didn’t recognize him at first, but the words gave him away.⁵

The mask came soon after. At first it was a plastic gladiator faceplate, later replaced by the steel design modeled after Marvel’s Doctor Doom. The mask became protection, a way to work without exposure. “The character himself, DOOM, will always have the mask. No one will ever see him without the mask… I’m not DOOM. I just write as this evil super-villain rapper named DOOM,” he said.⁶ The mask let him work again, unseen and without the pressure of recognition.

Operation: Doomsday (1999) marked his return and the creation of a character built to endure where Daniel could not. The beats were raw, built from soul samples and cartoon fragments, lo-fi and direct.⁷ His rhymes folded jokes, pop culture, and mourning into a single voice. “Doomsday” carried the loss inside steady tempo and plain delivery.⁸

Song: “Doomsday” (Operation: Doomsday, 1999)

Pour: Old Forester 1920 Prohibition Style, Kentucky, 115 proof

The track moves slow and rough, rhythm cut from pain but steady in tone. Old Forester 1920 matches that balance, heat and sweetness held tight. Both show how control can sound unpolished and real.

King Geedorah

By 2003, the mask was constant now, but he refused to stay inside one voice. Out of that discipline came King Geedorah, drawn from the three-headed dragon in the Godzilla films. The name fit the idea. “Geedorah is like from another planet, so he looks at the world differently,” he said in the Red Bull Music Academy lecture.⁹ The project gave him room to step back and build instead of perform.

Under the Geedorah name he produced almost the entire record, controlling arrangement, pacing, and tone. Guest MCs carried most verses while he appeared through fragments, samples, and short interludes. That choice wasn’t absence; it was direction. He once described the process as “letting the story tell itself,” a method closer to film editing than rap sequencing.¹⁰ The record felt distant because it was meant to.

Take Me to Your Leader (2003) moved with cinematic precision, thick drums under dialogue from 1960s science-fiction reels.¹¹ The mood was darker and heavier than Operation: Doomsday, less confession, more design. It was the sound of DOOM treating the studio as laboratory, one head on the mic, the others mixing, looping, and cutting.

Song: “Fazers” (Take Me to Your Leader, 2003)

Pour: Angel’s Envy Port Cask Finish, Kentucky, 86.6 proof

“Fazers” floats on repetition, confidence inside confusion. Angel’s Envy mirrors that tension, sweet from the port cask then dry and grounded at the close. Both reward patience; both make sense only once you listen past the surface.

Viktor Vaughn

If King Geedorah showed distance, Viktor Vaughn showed impulse. DOOM described the persona as “an eighteen, nineteen-year-old whippersnapper who thinks he knows it all.”¹² Vaughn was the younger version of the villain, still sharp but reckless. The name itself played on Victor Von Doom, the real name of Marvel’s Doctor Doom, tying the mask directly to its source.

Vaudeville Villain (2003) was the first of two albums under the alias. DOOM used faster cadences, darker production, and harsher textures than in his earlier work. He called it “like another dimension… in his dimension technology might’ve been a little further along.”¹³ The record sounded that way: cold synths, clipped drums, metallic space between lines.

The second project, Venomous Villain (2004), carried the idea further. Vaughn rapped with less patience and more edge, turning confrontation into rhythm. The two albums together formed a mirror to DOOM’s larger mythology. They weren’t experiments; they were extensions of the same architecture, proof that his style could bend without breaking.¹⁴

Song: “Vaudeville Villain” (Vaudeville Villain, 2003)

Pour: Rittenhouse Rye Bottled-in-Bond, Kentucky, 100 proof

The track moves fast, syllables stacked tight against static. Rittenhouse Rye carries the same urgency, spice forward and quick to heat. Both hit hard, leave a mark, and finish clean enough to go again.

Madvillain

If Viktor Vaughn was restlessness, Madvillain was focus. In 2004, DOOM joined producer Madlib to create Madvillainy, a record that redrew what underground hip-hop could sound like.

The sessions took place in Los Angeles at Stones Throw Records. Madlib worked in his home setup, surrounded by records and gear, keeping the process loose and intuitive—more vibe than plan.¹⁵ That looseness gave the record its shape. Verses came short, beats ended mid-idea, and the result felt like eavesdropping on two craftsmen building in real time.

The album is full of compression and density. “He has his own sound that you can’t duplicate,” DOOM said of Madlib at the Red Bull Music Academy.¹⁶ “It made me step my game up.” The respect was mutual. Madlib matched DOOM’s precision with unpolished beauty, vinyl hiss, clipped samples, uneven loops. Together they built a sound where every imperfection served rhythm.

Madvillainy became a turning point in DOOM’s mythology. The mask was now complete, behind it, he worked without pause or spectacle. The record’s impact came from its craft, not its surface.¹⁷

Song: “Figaro” (Madvillainy, 2004)

Pour: Elijah Craig Barrel Proof, Kentucky, 126 proof

“Figaro” is built on rhythm inside rhythm, bars turning against each other like gears. Elijah Craig Barrel Proof shares that complexity, rich and layered, heavy enough to slow you down. Both reward attention, not speed.

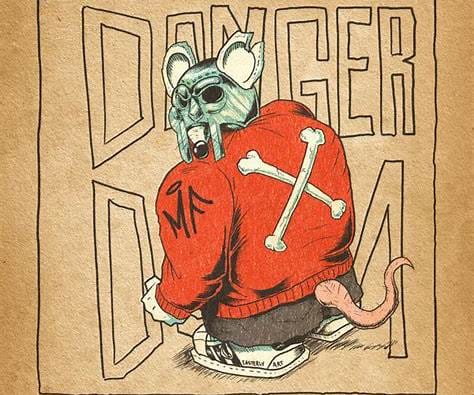

Danger Doom

By 2005, DOOM’s mask was already legend. His next collaboration, The Mouse and the Mask, recorded with producer Danger Mouse, expanded that legend into a new format. The record connected hip-hop with Adult Swim, blending satire, cartoons, and lyric discipline in one frame.

In interviews from that period, DOOM described the project as “fun, but still villain work.”⁸ That balance showed throughout the record. Danger Mouse’s production used crisp drums, bright samples, and cinematic layering while DOOM delivered verses packed with inside jokes, cultural references, and coded rhythm. The writing moved with precision even when the tone turned absurd.

Released through Epitaph Records, The Mouse and the Mask carried voices from Aqua Teen Hunger Force and Space Ghost Coast to Coast. It reached new listeners but kept DOOM’s structure intact. Every rhyme sat inside tight production, every line built from control. The album proved that humor could serve technique, not replace it.

Song: “A.T.H.F.” (The Mouse and the Mask, 2005)

Pour: Woodford Reserve Double Oaked, Kentucky, 90.4 proof

“A.T.H.F.” runs on clarity and timing, each pause deliberate, each punchline placed to land clean. Woodford Reserve Double Oaked follows the same pattern, layered sweetness under char that builds slowly. Both prove that polish can coexist with depth when handled by steady hands.

DoomStarks

Some collaborations feel designed by rumor before they happen. When DOOM linked with Ghostface Killah, the idea carried instant gravity. Both were stylists, both lived in detail, both treated language as craft. Fans expected an album that would merge two of hip-hop’s most distinct worlds.

The project became known as DoomStarks, a name drawn from Ghostface’s “Tony Starks” persona and DOOM’s metal mask mythology. Around 2006, fragments began to surface: “Angeles,” “Victory Laps,” “Chinatown Wars.”²¹ ²² ²³ Each track showed chemistry built on mutual respect. Ghostface’s sharp storytelling met DOOM’s stacked rhymes without overlap.

Plans for a full-length record, rumored under the title Swift & Changeable, never reached release. Public updates from the time consistently pointed to scheduling and delivery delays rather than a finished album.²⁴ The music that did appear was enough to sustain the myth. “Victory Laps (Madvillainz Remix)” arrived in 2011, proof that even fragments from the pairing showed the precision of two artists working at full capacity.²³

The unfinished nature of DoomStarks added to DOOM’s legend. It became a story about potential, not absence. What surfaced showed two craftsmen at work, unhurried and exact, leaving enough behind to make listeners imagine the rest.

Song: “Victory Laps (Madvillainz Remix)” (2011)

Pour: Peerless Double Oak Bourbon, Kentucky, 108 proof

“Victory Laps” hits in layers, voices cutting through shifting rhythm. Peerless Double Oak carries the same build, char inside sweetness, strength under control. Both arrive in pieces that still feel complete.

JJ DOOM

By 2010, DOOM’s story had shifted again. After a trip to London, he was refused re-entry to the United States because he had never completed naturalization. Born in England but raised in New York, he found himself cut off from the city that had defined his sound. From that distance, he built a new collaboration with producer Jneiro Jarel, the partnership known as JJ DOOM.²⁵

Their album Key to the Kuffs (2012) was written and recorded in England. The production leaned colder, electronic, and tightly looped. In interviews from that period, DOOM spoke about how living abroad changed the way he wrote and listened to music, describing a new perspective shaped by distance from New York.²⁶ The verses carried London slang and references to British streets, yet the cadence stayed New York, precise, clipped, and grounded in swing.

Jarel’s beats worked like architecture: metallic percussion, layered synths, and sparse bass lines. The sound felt industrial rather than nostalgic, a mirror to DOOM’s new surroundings. Songs such as “Guv’nor” and “Banished” turned isolation into control, each bar measured and clean. The mask stayed, but the tone changed. From distance he sounded more deliberate, less playful, as if editing the world from a step away.

Key to the Kuffs stood as proof that separation could sharpen focus. Exile did not silence him, it refined him. Every sound on the record, the clipped snare, the low hum of synth, the exact pause between lines, spoke to an artist rebuilding craft under constraint.

Song: “Guv’nor” (Key to the Kuffs, 2012)

Pour: High West Double Rye (92 proof, Utah), sharp spice, dry finish, structured complexity; widely available in U.S. markets.

NehruvianDOOM

By 2014, DOOM’s catalog spanned decades and aliases. Instead of looking backward, he turned toward a new generation. The collaboration with young New York MC Bishop Nehru became NehruvianDOOM, a project built around mentorship as much as music.

Their album NehruvianDOOM (2014) ran nine tracks, produced almost entirely by DOOM. His beats carried the slow swing and grit familiar to longtime listeners but framed Nehru’s sharp, unhurried flow. In interviews that year, DOOM spoke about wanting to create music younger artists could build on, keeping the sound fresh for the next generation.²⁸ The statement defined the project’s purpose: to hand down craft rather than nostalgia.

The sessions showed DOOM in a new role. Where earlier records hid the man, this one revealed the teacher. Nehru’s delivery mirrored the patience DOOM had once learned through loss and distance. The production was tighter than Key to the Kuffs, less experimental than Madvillainy, but still unmistakably his, samples stacked in low fidelity, rhythm exact, and humor folded into precision.

NehruvianDOOM proved that legacy could be structural, not symbolic. DOOM built a space for younger voices while maintaining the standard he set decades earlier. It was a reminder that the villain persona could evolve without softening, and that mentorship could function as another mask, one designed for continuity.

Song: “Darkness ” (NehruvianDOOM, 2014)

Pour: Kings County Peated Bourbon, Brooklyn, 90 proof

“Darkness (HBU)” opens with haze, then resolves into clarity. Kings County Peated Bourbon mirrors that tone, gentle smoke over soft sweetness. Both show how the new can respect the old without imitation.

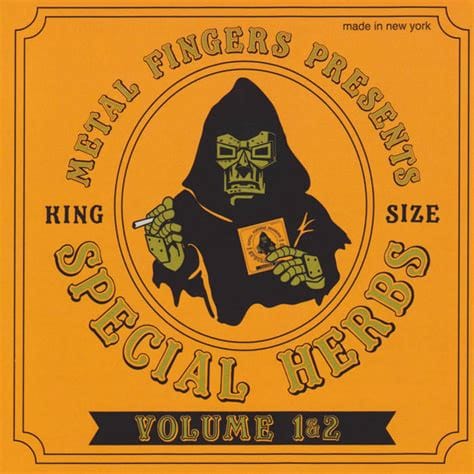

Metal Fingers

Behind every alias stood another identity, quieter but essential: Metal Fingers, the producer. Where MF DOOM was the voice, Metal Fingers was the builder. Under that name, he released the Special Herbs series between 2001 and 2005.³¹ ³² The collection of instrumental volumes revealed his method in its purest form.

Each track took the name of an herb or spice such as Fenugreek, Mugwort, or White Willow Bark. The titles read like an apothecary catalog.³¹ The beats were raw and meditative, drawn from soul, jazz, and film scores, edited with precision that made imperfection part of the rhythm. In the Red Bull Music Academy lecture, he described keeping the process simple, letting loops and small adjustments guide the structure, and leaving space when it served the feel.³³

The Special Herbs records became blueprints for his vocal albums. Fragments from them reappeared later under new titles, showing how he treated production as an evolving archive rather than a finished product.³² This recycling embodied refinement. Each return to a sample made the loop sharper and the timing more exact.

Metal Fingers showed the craftsman side of DOOM’s mythology. He worked quietly, assembling sound the way a distiller blends grain and char. The mask may have been his symbol, but the beats were his fingerprint.

Song: “Arrow Root” (Special Herbs, Vol. 1, 2001)

Pour: Four Roses Single Barrel Bourbon, Kentucky, 100 proof

“Arrow Root” feels smooth but off-center, melody steady while rhythm drifts. Four Roses Single Barrel follows that shape, clean entry, slow bloom, finish that lingers without burn. Both reward focus over speed.

The Villain’s Craft

What set DOOM apart was the way he built with words. His rhyme structure was dense and deliberate, packed with internal connections that folded across bars. Critics often called it abstract, but DOOM described his writing as patterned and mathematical, built on rhythm and internal logic rather than spontaneity.³⁴ His verses sounded free, yet every syllable landed by design.

He treated sound the same way. Sources ranged from 1970s cartoons to jazz records to obscure film dialogue. What most producers would skip, he transformed into foundation. The Special Herbs instrumentals showed how he refined those fragments until rhythm and sample fused. In interviews he explained that mistakes often stayed in the final mix, not by oversight but by choice. The roughness was part of the structure.³⁵

Even his live performances fit the mythology. Sometimes stand-ins wore the mask and performed in his place. When questioned, DOOM framed it as theater and continuity, saying the mask was the character and the act was part of the show’s design.³⁶ For him, the mask was never disguise; it was separation, a way to keep the art independent from the artist.

Through all of it, the focus stayed on craft. The vocabulary, the loops, and the precision of timing each existed to serve the work, not the image. In DOOM’s world, authenticity came from execution, not exposure.

Song: “Beef Rapp” (MM..FOOD, 2004)

Pour: Wild Turkey Rare Breed, Kentucky, 116.8 proof

“Beef Rapp” turns satire into technique, rhythm built from chaos but held in time. Wild Turkey Rare Breed mirrors that control, bold and layered, unfiltered but balanced. Both prove that refinement can exist inside raw form.

Later Years

During the 2010s, DOOM released less but his reach widened. Collaborations continued through Metal Face Records, reissues appeared across independent labels, and his fingerprints spread through the underground. He recorded with Bishop Nehru, Westside Gunn, and Czarface, each collaboration showing that the mask still shaped new work, even from a distance.³⁷

On December 31 2020, his wife Jasmine announced that DOOM had died two months earlier, on October 31. “The greatest husband, father, teacher, student, business partner, lover, and friend I could ever ask for,” she wrote. “Thank you for showing me how not to be afraid to love and be the best person I could ever be.”³⁸ The statement, posted on his verified Instagram and confirmed by major outlets, ended a year of speculation. Within minutes, tributes filled every channel of hip-hop media.

Artists, producers, and fans treated the loss as more than a headline. Madlib said that DOOM was his favorite MC, hands down.³⁹ Ghostface Killah called him one of the most creative minds to ever bless the mic.⁴⁰ Tyler, The Creator wrote that DOOM was the reason he rapped the way he did.⁴¹ Across generations, the tone was the same: respect, disbelief, and gratitude for an artist who had changed what independence could mean.

His estate continues to oversee his catalog with precision. The label remains active, the notebooks still surface, and the beats keep circulating through new work. DOOM’s system of aliases and archives made that possible. What he left was not a monument but an engine, one still running, still feeding what came after him.

Song: “Rhymes Like Dimes” (Operation: Doomsday, 1999)

Pour: Russell’s Reserve 10 Year Bourbon, Kentucky, 90 proof

“Rhymes Like Dimes” plays loose but exact, humor wrapped around discipline. Russell’s Reserve 10 carries that same patience, oak and vanilla balanced through age. Both work without spectacle and prove endurance is a craft of its own.

The Super Villain’s Legacy

DOOM never hid to disappear; he hid to keep the work intact. Every alias, every record, and every voice formed part of a machine that kept running while the rest of hip-hop chased light. Zev Love X carried the spark, MF DOOM built the architecture, King Geedorah expanded range, Viktor Vaughn bent time, and Metal Fingers built the floor. Each name had a task, each sound a tool.

When The New Yorker asked him what the villain meant, he said, “The villain represents anybody. Everybody. Anybody can wear the mask.”⁴² The mask turned anonymity into utility, a shield for the music, not for the man. Behind steel, he could shift voices, test forms, and disappear without stopping the engine. That decision defined two decades of independent hip-hop.⁴³

The catalog behaves like a rickhouse. Each album holds its own character, yet together they form an ecosystem: barrels stacked in rows, proof adjusting with time and temperature. Operation: Doomsday sounds young, high and sharp. Madvillainy sits dense and settled. MM..FOOD carries sweetness under heat. JJ DOOM and NehruvianDOOM sound like the air between barrels, space turned into rhythm.⁴⁴ Each record breathes at its own rate, but all share the same foundation of grain, char, and patience.

His writing followed the same logic. Lines folded into each other, recycled, aged, stripped, and used again. “I write in shapes,” he said in an interview with *The Wire.*⁴⁵ “Once you catch it, you see it.” Every rhyme had another waiting inside it, the way a seasoned barrel keeps the trace of the last fill.⁴⁶

Above it all worked the Super Villain. The laugh, the calm, the exact timing. He directed the machinery, keeping control without spectacle. He built consistency , where others built image. Every release carried his internal standard of clarity, repetition, and precision.

Now, the shelf remains. A rickhouse of barrels, air thick with char and history. Each persona a vessel, each record its own proof. None perfect, all necessary. The longer they sit, the deeper they get. The heat in the wood rises, the vapors move, and the sound keeps aging whether anyone touches it or not.

That is the work DOOM left behind. Not a product, not an image, but a method that still produces. He built a world where craftsmanship can live without exposure. In a culture that prizes speed, he left instruction for patience. In a market that sells faces, he left a mask that anyone can wear. What survives of him is not mystery; it is process—the loops, the patterns, the rhythm that makes structure sound human.

For the ones still cutting, looping, blending, or bottling, the lesson is the same. Control your craft, protect your pace, and trust what time will do.

Song: “Coffin Nails” (Born Like This, 2009)

Pour: Maker’s Mark 46 Bourbon, Kentucky, 94 proof

“Coffin Nails” grinds slow, rhythm scraping against steel. Maker’s Mark 46 answers with depth drawn from charred oak, warmth edged by spice. Both prove that control can sound rough and still finish clean.

Sources

- Red Bull Music Academy, MF DOOM Lecture – Toronto 2011.

- The New Yorker, “The Mask of MF DOOM,” Ta-Nehisi Coates, Sept 2009.

- Pitchfork, Jeff Weiss, “MF DOOM Remembered,” Jan 2021.

- AllMusic, Artist Page – KMD.

- Elektra Records Press Statement / Archive, 1993.

- HipHopDX, “How KMD Was Dropped and Reborn,” 2011.

- Stones Throw Records, Operation: Doomsday Reissue Liner Notes, 2011.

- Red Bull Music Academy, Toronto Lecture Transcript, 2011.

- Pitchfork, Obituary Feature, Jan 2021.

- Red Bull Music Academy, Toronto Lecture, 2011.

- Big Dada / Ninja Tune Records, Take Me to Your Leader Press Kit, 2003.

- Pitchfork, Album Review, 2003.

- Sound on Sound, “MF DOOM Production Notes 2003–2004.”

- Lex Records, Internal Release Notes, 2003.

- Fact Magazine, “MF DOOM – A Study in Characters,” 2010.

- Stones Throw Records, Madvillainy Liner Notes, 2004.

- The Guardian, Alexis Petridis, “Madvillainy Review,” Mar 2004.

- Red Bull Music Academy, Toronto Lecture, 2011.

- The Wire, Issue 253, Mar 2005.

- Epitaph Records, The Mouse and the Mask Press Release, 2005.

- NME, Album Review, Oct 2005.

- Billboard, Chart History Report, 2005.

- Interview Magazine, “Ghostface Killah & MF DOOM Discuss Swift & Changeable,” 2006.

- Stones Throw Records, “Victory Laps (Madvillainz Remix) Press Sheet,” 2011.

- Pitchfork, News Post – “DOOM & Ghostface Killah Project Details,” 2011.

- Lex Records, Key to the Kuffs Press Release, 2012.

- The Guardian, “JJ DOOM: Key to the Kuffs Review,” Aug 2012.

- NME, “MF DOOM Denied Re-entry to U.S.,” 2010.

- Genius, JJ DOOM – Key to the Kuffs Album Details, 2012.

- Clash Magazine, “Bishop Nehru on Working with MF DOOM,” 2014.

- Hypebeast, “NehruvianDOOM Album Review,” Oct 2014.

- Discogs, NehruvianDOOM – NehruvianDOOM (Sound of the Son), 2014.

- Rhymesayers Entertainment, “Metal Face Records and Rhymesayers Re-Release Special Herbs Collection,” 2025.

- Archive.org, Special Herbs – The Box Set Vol. 0–9, 2005.

- Paste Magazine, “Special Herbs Is a Daunting but Fascinating Image of MF DOOM,” Jan 2021.

- The Wire, Issue 253, Mar 2005.

- Paste Magazine, Jan 2021 (cited above).

- Stones Throw Records / Rolling Stone Excerpt, “Everything We Do Is Villain Style,” 2009.

- Rolling Stone, “MF DOOM’s Legacy Lives On Through His Collaborators,” Jan 2021.

- BBC News, “Rapper MF DOOM Dies Aged 49, Wife Confirms,” Dec 2020.

- NPR Music, “Madlib Remembers MF DOOM,” Jan 2021.

- Rolling Stone, “Ghostface Killah Pays Tribute to MF DOOM,” Dec 2020.

- Billboard, “Tyler, The Creator & More Pay Tribute to MF DOOM,” Jan 2021.

- The New Yorker, “The Mask of MF DOOM,” Ta-Nehisi Coates, Sept 2009.

- Pitchfork, “Remembering MF DOOM,” Jan 2021.

- Stones Throw Records, Album Liner Documentation (1999–2004).

- The Wire, Issue 253, Mar 2005.

- Red Bull Music Academy, MF DOOM Lecture – Toronto 2011.